Makini Chisolm-Straker, MD: Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Emergency Medicine PGY3

Liberia: September 2011

Down the driveway, the design of opulence awaits. Tucked safely from the bustling Tubman Boulevard, gated from the blind beggars and one-legged tramps,

protected from the direct blare of traffic sits John Fitzgerald Kennedy Hospital, once a gem of Liberia, now a relic of grandeur. Dusty, dingy, frankly

filthy and grey with a dead sort of brown overtone lolls the cement 4story building. JFK is now a shell of a thing, filled with the dead ghosts of shiny

new gadgets from half a century prior. Now the sounds of kwarshiorkor children echo down long, cavernous halls; patients are hungry for salvation or lunch.

Families surround the pocked walls; they are crouched praying, scrounging for money to pay for the best in bare-bones care wailing against the

unrelentingly truth of death.

Inside, in medical emergency a smell that is distinct reigns, wafts, settles and ingratiates itself into your pores. It seems to be the scent of

tuberculosis, malaria, AIDS-wasting syndrome, liver failure and old-man urine, marinated in the dank of an unconditioned, unventilated room whose floor is

decorated with hemoptysis and sputum, spilled urinals that hold mysterious frothy contents, dripped quinine and cockroaches unabashed by their nakedness in

the light. It is here the nurse sits at her station (a Mayo stand, actually), in all white; she will work for 12hours and not a stain will rise against her

pristine display of cleanliness. I've seen just one wash her hands (and dry them on the curtains, as there are no towels). Where does all this dirt and

grit under my manicured nails get to on theirs?

Inside trauma emergency a separate and rank scent smacks, as you open the top half of the stable doors; this one is familiar from home but concentrated,

multiplied and tainted by a hotter, even more poorly ventilated quarantine. It is blood and pus of infected wounds and stale emesis and sweat; the cries of

impressively cooperative children who flail every limb but the affected during dressing changes; the rattles of unconscious men with tubes in all orifices,

save their trachea, waiting for a coveted death that each day seems just a few hours away; the banter of nurses huddled near the singular fan and

Rihanna-playing phone that lays next to the radio droning the rolling tally of election results.

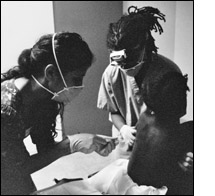

You can't feel or be clean in a place like this. But there are small differences to be made and some lives can be saved. Today, we saved one, for sure.

Lulu made the deliverance by answering the noble call of service and care. I told Bendu, the model nurses should be formally recognized to show the others

how to sculpt themselves in the expectation that with time and effort the Liberian people will stop needing volunteers.